September 25, 2019

Note: A video of Sarah Birmingham Drummond’s inaugural address is available here. A video of the whole service is also available here.

A slideshow of images from the event can be found here: Slideshow - The Installation of Sarah Birmingham Drummond.

In Defense of Seasons

Good afternoon. As I look out at this assembly, I see people I love who have surrounded me with  support and care through all the seasons of my life. I see my family of origin, and the cherished family I’ve built; my friends from different times in my life, including my bright college years; colleagues from many settings of ministry, past and present; and I see students – so many students – who remind me what this is all about. Thank you all for being here.

support and care through all the seasons of my life. I see my family of origin, and the cherished family I’ve built; my friends from different times in my life, including my bright college years; colleagues from many settings of ministry, past and present; and I see students – so many students – who remind me what this is all about. Thank you all for being here.

support and care through all the seasons of my life. I see my family of origin, and the cherished family I’ve built; my friends from different times in my life, including my bright college years; colleagues from many settings of ministry, past and present; and I see students – so many students – who remind me what this is all about. Thank you all for being here.

support and care through all the seasons of my life. I see my family of origin, and the cherished family I’ve built; my friends from different times in my life, including my bright college years; colleagues from many settings of ministry, past and present; and I see students – so many students – who remind me what this is all about. Thank you all for being here. There are so many people to acknowledge for putting this day of festivities together. Allow me to single one out: my colleague Ned Parker, who chaired the committee that planned this event with both meticulousness and creativity. We’ve been through a lot together, my brother; your work, and your very being, are a gift to the school we love. Thank you, Ned.

The theme for this service is seasons, with a special shout-out to the magic month of September. You might wonder, Why September, besides the date on the calendar? The answer is renewal. Whereas secular culture celebrates the new year on January one, accountants mark it on July one, and Christians say it’s the first Sunday of Advent, educators look to September as the start of all things new. This month is our happy new year, and this service marks a new beginning. You also might wonder, Why the theme of seasons? That question will require more attention.

About ten years ago, a blizzard hit New England at the end of October. Arborgeddon, as the storm was later dubbed, was particularly devastating because of the damage it did to trees. Since they still have too many leaves on them in October to withstand the weight of snow, trees fell on houses, cars, and roads. Connecticut was hit hardest, probably because Nutmeggers like their trees more than their power lines. My parents lost electricity for 10 days, and my sister for almost three weeks. We had somewhat less damage in Massachusetts, but still, we lost some beautiful trees.

As the winter of Arborgeddon began to subside, I collaborated with the dean of our chapel in Newton, Mary Luti, on our school’s Ash Wednesday service. We asked students to gather sticks from the grounds of our campus and organized the service as a memorial to the trees that had died. I still have one of those sticks, as we handed them out with a blessing as we imposed ashes on foreheads: dust you are, and to dust you shall return.

The illustration I used in my sermon that day came from a visit my husband Dan and I took to my home town of Suffield, CT the Thanksgiving after Arborgeddon. We’d gone to a park where I’d spent time in my childhood and found that dozens of gigantic trees had fallen, their root balls a story high in the air. Many other trees were damaged but alive. We could tell which trees were living and dead by their leaves. If the colors were the ones associated with mid-fall, the tree was frozen in time; dead. If the tree was bare, it was alive, having responded to nature’s call to change seasons. A tree’s capacity to honor seasons is essential to its being alive.

As many of you know, our family lost my father this past February. He’d been declining in health slowly, and then all-of-a-sudden, over the course of about five years. My mother took wonderful care of him, but his illness took a toll on her health, most notably in the form of a bad back made worse by the literal heavy lifting of eldercare.

In August, my mother went under the knife and got some hardware to shore up her spine. After her surgery was over, my sister Wendy and I were allowed a few minutes with her in the recovery room, but then we waited several more hours. She was slow coming out of the anesthesia, and where Wendy was staying overnight at the hospital, God bless her, I’d planned to go home to sleep. I imposed on the recovery room staff for one more visit before leaving for the evening.

I was only allowed a few minutes, during which time my mother told me a story that she now doesn’t remember telling, high as a kite as she was (don’t worry; she knows I’m sharing this). My mother told me she went to visit my father’s grave the day before her surgery. She stood at his graveside and talked to him about what was about to happen. Then she got in her car, closed the door, and screamed. She screamed in anger that he’s gone, screamed because she’d lost some of her own health while caring for him, and screamed over her pain in body and spirit since his departure from this life.

After some serious and lengthy screaming, she felt better. She turned the engine over and proceeded to drive home, waving pleasantly and the other visitors at the cemetery, wondering blithely what they’d heard, and how they’d made sense of it. From her haze, my mother told me she could, at that moment, feel a new season begin. Together, we agreed, through our tears, that seasons are good. The only proof we need of Christ’s resurrection is the way resurrection happens during our lives, again and again.

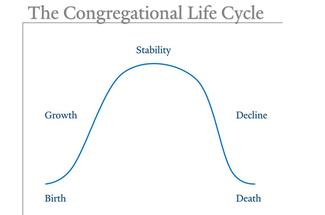

“Congregational Studies” is an area of inquiry about which I know little but have many thoughts; I know what you’re thinking: typical Yalie. Those who study congregations generally agree that churches, like people, have life cycles. They’re born, develop, and grow. Then they stabilize and decline in a cycle that lasts about three generations. Here in New England, we know that churches often last much longer than the 75 or so years that would constitute three generations. Many of our churches are pushing 350 and going strong.

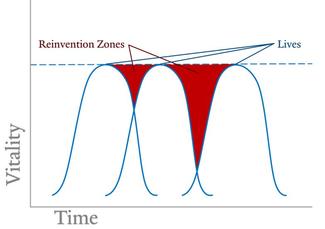

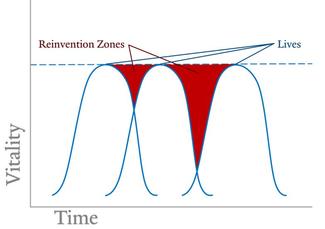

“Congregational Studies” is an area of inquiry about which I know little but have many thoughts; I know what you’re thinking: typical Yalie. Those who study congregations generally agree that churches, like people, have life cycles. They’re born, develop, and grow. Then they stabilize and decline in a cycle that lasts about three generations. Here in New England, we know that churches often last much longer than the 75 or so years that would constitute three generations. Many of our churches are pushing 350 and going strong.  The longer duration doesn’t mean that the old churches’ life-cycle curve is wider; it means those congregations have reinvented themselves. As older churches declined, they remembered who they were and considered what they needed to become in the context of their day. Like trees, churches that respond to seasons are the ones that are still alive.

The longer duration doesn’t mean that the old churches’ life-cycle curve is wider; it means those congregations have reinvented themselves. As older churches declined, they remembered who they were and considered what they needed to become in the context of their day. Like trees, churches that respond to seasons are the ones that are still alive. If September represents a new start, Andover Newton’s renewal here at Yale Divinity School is our September. Andover Newton’s educational program at YDS reflects the most current knowledge we have about what it takes to be an effective faith community leader in the locally-governed traditions. Our school is the only small-c congregational seminary embedded in the divinity school of a world-class university. Those who don’t want to choose between a seminary’s focus on ministerial formation, and a divinity school’s capacity to educate them theologically and intellectually find their perfect fit here. Our offices are renovated, our staff strong, our faculty brilliant, our student leadership self-perpetuating, and our students just ridiculously awesome. The future looks bright, and we’re ready to make a serious difference in the ministries our graduates serve, carrying out a strikingly-consistent mission in a new place, in a new way, in a new day.

This September for Andover Newton is by no means its first. As the oldest graduate school of any kind in the US, we’ve had lots of Septembers, on average every three generations. Many of you know Andover Newton’s history, but for those who don’t, and those who never tire of it, let’s consider some milestones. Andover Seminary was born in Cambridge, when Henry Ware – a Unitarian – ascended to the Hollis Chair of Divinity at Harvard, giving the Calvinist orthodoxy a scare. Timothy Dwight, the President of Yale at the time, and grandson of our tradition’s patron theologian Jonathan Edwards, traveled to Cambridge to stoke dissent among faculty members. They went on to form a break-away seminary to educate Congregational ministers in Andover, MA, out in the middle of the woods.

Less than 20 years later, the leaders of the First Baptist Church in Boston decided they, too, wanted to create a seminary out in the middle of the woods to educate Baptist clergy. They founded Newton Theological School, and its first President, and three of its first five faculty members, were imports from Andover. The first graduates had transferred from Andover.

Over the years, both schools educated the clergy who served the churches of New England, as well as missionaries who ventured all over the nation and world. The crossover of faculty, students, and ideas between Andover, Newton, and later Yale Divinity School, was constant and rich. Do note that YDS is the youngest of this second-great-awakening family’s three kids.

Andover and Newton respectively went through season after season, shaped by the culture around them, which was of course changing too. One such change of seasons has become the source of much fascination for me lately because it led to the most recent other time our school moved and partnered; I’m speaking of the solstice that brought Andover together with Newton.

The coming together of Andover Newton resulted from many decisions, some seemingly small, made over the course of more than a hundred years. The first of those decisions took place when the breakaway faction from Harvard chose the middle of which nowhere would become its new campus’ location. The group chose Andover, MA because one of those former-Harvard-faculty renegades, Eliphalet Pearson, was married to a Phillips, and the Phillips family was creating a school in Andover for boys. Andover Seminary and Phillips Academy coexisted for a century, and at first the seminary was at first the bigger and stronger partner. Over time, however, the prep school grew in influence, and the Andover faculty felt squeezed. They decided to give things with Harvard another try.

Among the best pieces of advice my mentor Peter Gomes ever gave me was this: “Follow in anyone’s footsteps but your own.” This advice would have helped the Andover faculty, as their attempt at reconciliation didn’t take. Andover brought money, books, and a faculty to Cambridge, but their key donors were nonplused. Those donors had given Andover money not to be at Harvard. Donors’ descendants took the matter to court claiming violation of their foreparents’ intent. The Supreme Judicial Court of the State of Massachusetts, the same entity that approved Andover Newton’s partnership with Yale just last December, shut the Andover operation in Cambridge down.

Harvard absorbed all but one member of Andover’s faculty. The one they spat out was the Samuel Abbot Chair, as it represented a theological perspective Harvard wasn’t planning to perpetuate. Every time you think about how much you appreciate Mark Heim, thank Harvard for cutting the Abbot Chair loose. Andover lay fallow for five full years, with money in the bank, one named chair, a board determined to carry out a mission to educate clergy for Congregational churches, and no school.

Newton was, at that moment in the early 20th Century, in a different kind of predicament. They had students and a beautiful campus, but they were running out of money. In his memoir Turns Again Home, Newton President Everett Carleton Herrick writes that he became President at a time when the school was trying to cope with a serious setback. The Northern Baptists had attempted a campaign that promised but then failed to deliver a much-needed influx of capital. Herrick went to New York City to call on Mr. Rockefeller, as so many did, securing enough support to stabilize the school temporarily. Herrick describes the situation as “little short of desperate.”

Andover and Newton’s fates began to intertwine first with a phone call that took place in the late 1920s or early 30s. Herrick writes,

“One day, I was talking over the telephone with Dr. Ashley D. Leavitt, who had such an outstanding pastorate at Harvard Congregational Church, Brookline. He was one of the Andover Visitors. In the course of the conversation he said, “Have you ever thought about the possibility of some kind of tie-up with Andover? You know we have got to do something and go somewhere.” That was actually the first seed of the idea sown in my mental field. I called up my good and guiding friend, [Massachusetts Supreme Court Justice] Fred Field, and asked, “What about this Andover situation? You have been a master in this controversy and must be the best authority I know.” Then I told him of my conversation with Dr. Leavitt. His answer was an illustration of the judicial mind. The gist of what he said was that of course you can try anything within reason and I wish you good luck. There was nothing enthusiastic or unguarded about that statement. To use an overworked word, I started out to explore the idea [and] found that… others… had already thought of it.”

Herrick goes on to write that during tentative yet increasingly-hopeful negotiations between the two schools’ trustees, Newton’s donors stepped up and lifted the school out of crisis mode. By then, however, the Visitors from Andover and Newton alike had found new reasons to come together. Whereas Newton was at first in talks because of money woes, and Andover was at the table because it needed someplace to go, new potential benefits of teaming up emerged with every meeting. Herrick writes he stayed with the negotiations for two reasons: first, to set an example of denominational cooperation; and second, to offer students the strongest possible faculty.

Change around just a few names, and you’re reading the story of negotiations between Andover Newton and Yale. One story Herrick shares about the Newton and Andover negotiations made me laugh out-loud with recognition. A member of Newton’s faculty asked in a meeting what the new seminary’s school colors might be. A particularly witty professor quipped that he thought Andover’s colors must be black and blue. We had the same kind of conversation about new school colors here not two years ago. For your information, Andover Newton’s colors were purple and navy blue, but we’ve changed our blue to match the brighter shade that’s Yale’s.

Andover was black and blue, but not dead, because it had a mission to fulfill. It’s our mission that has pulled our school up out of every decline, and into every new season of its long and meaningful life. In our school’s last days in Newton, MA; when Andover Newton was running out of options, and needing to make a big change; I took more comfort than you could know in the school’s history of reinvention in favor of mission. We had to gradually close our campus due to a perfect storm of enrollment decline; deferred maintenance; well-founded nervousness on the part of donors; and our determination that students needed to take on less, not more, debt. We found a partner in our old friend and baby sibling, Yale Divinity School, which cared about all the same things we did. We joined forces and are finding renewal, but these years haven’t been easy, which many in this room could describe more adequately than I. But our mission needs to live on, so we tend and cultivate and serve.

That “strikingly consistent mission” I mentioned earlier? We educate clergy. “Educate” means something different in each generation, and so does “clergy,” but the basic idea remains the same. God calls individuals out of faith communities to become God’s servants in ministry. There’s no saying “no” to that call, try as one might, so we all need to support called persons by providing them with education, nurture, formation for leadership, and colleagues.

The team that put together Andover Newton’s most recent mission statement in 2013 included my predecessor Martin Copenhaver, who was at the time a trustee; my birthday-celebrating colleague Gregory Mobley; our dearly departed trustee Sylvia Ferrell-Jones; and myself. It reads as follows: “Deeply rooted in Christian faith, and radically open to what God is doing now, Andover Newton educates inspiring leaders for faith communities.”

Let’s look again at these life-cycle curves, especially the red space. That space is where I propose we need to become obsessed with mission. It’s the mission that guides us from the downward slope, into a time of discernment, and back into a period of new life and growth. If we discover our mission is no longer relevant, we should allow nature to take its course. But if the mission still matters, our call – from which we can’t turn away – is to rebuild. The red space also shows us the peril of waiting too long; we want less red before reinvention, in order that we might have conserved the energy needed for change.

Let’s look again at these life-cycle curves, especially the red space. That space is where I propose we need to become obsessed with mission. It’s the mission that guides us from the downward slope, into a time of discernment, and back into a period of new life and growth. If we discover our mission is no longer relevant, we should allow nature to take its course. But if the mission still matters, our call – from which we can’t turn away – is to rebuild. The red space also shows us the peril of waiting too long; we want less red before reinvention, in order that we might have conserved the energy needed for change. The ultimate reinvention for the sake of mission was the resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ. God sent Jesus among us to teach us that God wants us to love. That truth was too strong to die. The love of Jesus overcame the power of the state, the scorn of Jesus’ own people, and even the forces of death. Mini-resurrections, like the ones that happened to Jairus’ daughter, and Lazarus, and my mother, and every person in this chapel and watching this service online? Their very possibility came into the world through Jesus’ triumph over the grave.

In the case of Andover Newton Seminary at Yale Divinity School: the education of ministers is so important our school doesn’t have time to die. We’ll have our ups and downs, our black and blue bruises, but today we remember that our seasons haven’t been harbingers of death, but reminders we’re alive.

In a few minutes, I’ll be installed into a four-point call. I’ll have my ordained standing in a network of relationships that includes the United Church of Christ, my local church, Andover Newton Seminary at Yale Divinity School, and me. All have a stake in the upholding of Andover Newton’s historic mission of providing a learned clergy to renew society. This is my calling, to which I couldn’t say no if I wanted to, and to which I offer my heartfelt yes. Andover Newton Trustees, Dean Sterling, and this gathered community: thank you for this opportunity. I’ll give it all I have and all I am, with God’s help. Thanks be to God, and Amen.