George Washington Williams: A Biography by Prof. Gregory Mobley

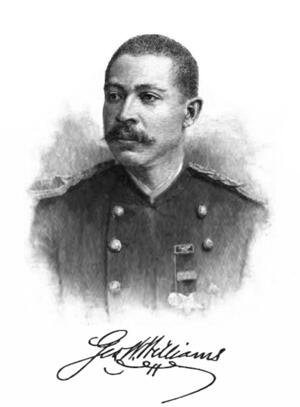

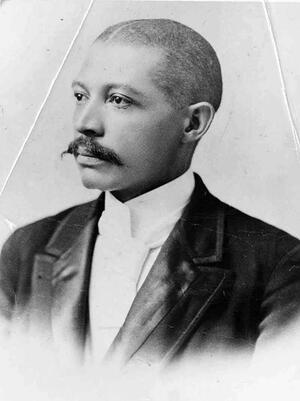

George Washington Williams

by Prof. Gregory Mobley

George Washington Williams is one of the unsung heroes of American history.

William’s significance for Andover Newton is that he became its first African American graduate when he received his degree from the Newton Theological Institute in 1874. William’s significance on the national and global stage as soldier, minister, politician, lawyer, historian, novelist, and journalist has rarely been acknowledged. Incomparable, intrepid, itinerant: the humanitarian, intellectual, and professional achievements produced by William’s wide-ranging, restless genius, all mark him as one of the great figures of the second-half of the 18th century. However, as his biographer, the esteemed University of Chicago historian John Hope Franklin asks about Williams: “Why is he such a deep, dark secret?” Andover Newton Seminary at Yale Divinity School seeks to honor this giant hidden in our history.

(Find a video presentation about George Washington Williams at the bottom of this page.)

Early Life and War Years (1849–1868)

George Washington Williams was born in southwestern Pennsylvania in 1849. As an African American teenager, he attempted to enlist in the Union army in his hometown of Newcastle, Pennsylvania, thirty miles north of Pittsburgh, in the summer of 1864. But they knew him there - and how old he was - so they told him to go home. He traveled to Meadville, fifty miles north, and enlisted in the Grand Army of the Republic under an assumed name. He was 14, hardly grown, skinny, and 5’4.”

George Washington Williams was born in southwestern Pennsylvania in 1849. As an African American teenager, he attempted to enlist in the Union army in his hometown of Newcastle, Pennsylvania, thirty miles north of Pittsburgh, in the summer of 1864. But they knew him there - and how old he was - so they told him to go home. He traveled to Meadville, fifty miles north, and enlisted in the Grand Army of the Republic under an assumed name. He was 14, hardly grown, skinny, and 5’4.”Wounded near Richmond, Williams recovered and fought at Petersburg. After the surrender his company was sent to Texas where, a month after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, the Civil War ended. Soon his wanderlust kicked in—it would not be the last time—and he deserted the army and fled to Mexico where he joined the revolutionary army seeking to overthrow the would-be Austrian colonizer Maximilian, a puppet European prince.

He arrived home back in Pennsylvania in 1867, but didn’t stay long before enlisting in the U.S. cavalry and becoming a drill sergeant posted to Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma in one of the African American regiments dubbed the “Buffalo Soldiers.” After a year Williams was honorably discharged from the 10th Cavalry with a wounded lung. Williams contended that he quit the cavalry because he had no taste for killing Native Americans.

Newton and Boston Years (1869–1876)

After stops at Quincy, Illinois, Hannibal, Missouri, and Washington, D.C., where he briefly enrolled in Howard University (then in its second-year of existence), Williams found his way to Newton Centre where he became the first African American student to enroll at the Newton Theological Institute in 1870.

Fourteen students entered Newton’s class of 1870, including graduates of Amherst, Brown, and Colby colleges. Williams had graduated from a different school. He had no degrees but two bullet wounds. He had received his education in a civil war, in a revolution, and in an attempted genocide on the Great Plains, as a, respectively, solider in the Union Army, soldier of fortune, and Buffalo Soldier.

By the time he graduated from the Newton seminary at age 24, he had caught up with and surpassed his classmates from prestigious New England colleges and was named commencement speaker for the class of 1874. He was ordained in the First Baptist Church in Watertown while at seminary.

After graduation from Newton, he was called to be pastor of Twelfth Baptist Church in Boston (the same church where Boston University seminarian Martin Luther King, Jr. would serve as student minister) and immediately wrote a history of that congregation started by fugitive slaves.

A year later he resigned his position and moved to Washington where he started an African American newspaper, The Commoner.

Ohio Years (1876–1882)

Williams moved to Ohio in 1876 where he became pastor of the Union Baptist Church in Cincinnati, wrote a newspaper column, and became active in politics in the party of Lincoln, the Republicans. After two years, he left the pastorate to become a lawyer, apprenticing—as it was done in those days—in the office of Alphonso Taft, Cincinnati’s leading lawyer, and father of a future president.

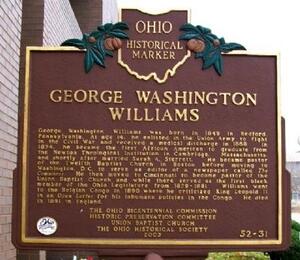

Williams moved to Ohio in 1876 where he became pastor of the Union Baptist Church in Cincinnati, wrote a newspaper column, and became active in politics in the party of Lincoln, the Republicans. After two years, he left the pastorate to become a lawyer, apprenticing—as it was done in those days—in the office of Alphonso Taft, Cincinnati’s leading lawyer, and father of a future president. (Click picture of the historical marker in Ohio for more information about its location.)

Two years later, Williams ran for and won election to the Ohio House of Representatives in 1880 and served a two-year term. Williams was the first African American congressional member in Ohio. The “George Washington Williams Room” at the Ohio State House memorializes his legacy there.

At thirty years of age, He moved to Columbus, where among his first activities was to file a bill to repeal the Ohio ban on interracial marriage, though it failed.

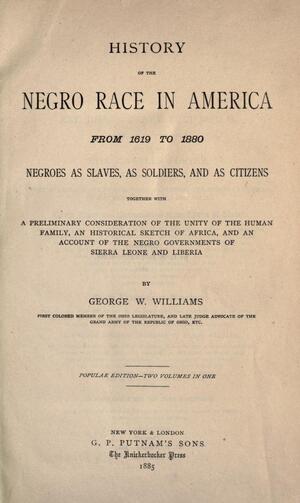

But within two years his curiosity had moved on and he began his great scholarly work, The History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1880, a 1000-page, two- volume work published in New York by G. P. Putnam’s Sons, favorably reviewed by the New York Times, the Atlantic and the Nation. Another tome followed, the History of the Negro Troops, published by Harper in 1887. His work inspired a senior at Fisk University who wrote in 1888 that Williams was “the greatest historian of the race.” The name of that college student was W. E. B. Du Bois. It has been said of Williams that he single-handedly started African American historiography. In the first of these works, Williams coined a phrase that caught on and to this day has become part of our vocabulary of prophetic protest. Williams wrote American slavery was not only an assault on enslaved Africans people, but represented a degradation of the entire human race. He called it “a crime against humanity.”

But within two years his curiosity had moved on and he began his great scholarly work, The History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1880, a 1000-page, two- volume work published in New York by G. P. Putnam’s Sons, favorably reviewed by the New York Times, the Atlantic and the Nation. Another tome followed, the History of the Negro Troops, published by Harper in 1887. His work inspired a senior at Fisk University who wrote in 1888 that Williams was “the greatest historian of the race.” The name of that college student was W. E. B. Du Bois. It has been said of Williams that he single-handedly started African American historiography. In the first of these works, Williams coined a phrase that caught on and to this day has become part of our vocabulary of prophetic protest. Williams wrote American slavery was not only an assault on enslaved Africans people, but represented a degradation of the entire human race. He called it “a crime against humanity.”Massachusetts Years (1883–1889)

Williams returned to Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1883 where he won admission to the Massachusetts bar. In these years he continued to write as well as speak throughout the country on civil rights and African American history. To get a sense of his contemporary significance in the 1880’s: when the 20th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation was celebrated in in 1884 in the nation’s capitol, Williams was selected as the keynote orator and spoke before a crowd of thousands. During this decade, Williams also wrote a novel, The Autocracy of Love, an interracial romance.

Williams returned to Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1883 where he won admission to the Massachusetts bar. In these years he continued to write as well as speak throughout the country on civil rights and African American history. To get a sense of his contemporary significance in the 1880’s: when the 20th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation was celebrated in in 1884 in the nation’s capitol, Williams was selected as the keynote orator and spoke before a crowd of thousands. During this decade, Williams also wrote a novel, The Autocracy of Love, an interracial romance.In 1885 Williams was appointed U.S. ambassador to Haiti in the final days of Republican Chester Arthur’s presidency. But Arthur’s successor, the Democrat Grover Cleveland blocked the appointment and, despite Senate confirmation, John E. W. Thompson, also African American, was given the posting. So Williams moved to Worcester.

The Congo (1889–1891)

Then, in 1889, Williams attended the International Anti-Slavery Conference in Brussels, Belgium as a correspondent for what came to be known as the Associated Press. There he interviewed King Leopold of Belgium who told Williams about his reputed civilizing work of Christian charity in the Congo. That’s all it took to inspire Williams to travel to the Congo in 1890 on a self-appointed mission to see if the Congo was a site where African Americans could repatriate. In the Congo, Williams made his most significant contribution to history. Williams discovered there what he described as a massive penal colony. Williams was the first recorded witness to the horror of European exploitation of Africa and Africans.

In 1890 Williams traveled from the western coast of central Africa into the interior, a journey taken a decade early by Henry Stanley, the self-promoting agent of King Leopold, famous for finding David Livingstone.

There he wrote his “Open Letter to King Leopold,” a sixteen-page indictment of the degradation of the Congolese people, the slave trading, and the barbarities done in order to rob Africa of ivory and rubber. Williams crossed paths with but did not meet an English writer, born in Poland, who was in the Congo at the same time in 1890 and who would forever bear witness to the savagery of Western colonizers in Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad.

Williams’ “Open Letter to King Leopold” was published in newspapers throughout America and Europe. But on his way back to the States from the Congo, at a stop in Blackpool, England near Liverpool, Williams died of pneumonia in 1891 at age forty-one.

Retrospect

What to make of the prodigious legacy of Williams who, in a mere four decades, was a barber (a trade he learned as a boy), soldier, clergyman, journalist, novelist, politician, historian, human rights activist, and lawyer? John Hope Franklin referred to Williams as “one of the small heroes of the world.”

George Washington Williams walked with giants: among his friends, acquaintances, and correspondents were Presidents Rutherford B. Hayes, Grover Cleveland, and Benjamin Harrison, Frederick Douglass, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. In 1890, an Indianapolis newspaper conducted a poll of the “Ten Greatest Negroes Who Ever Lived.” Williams was among them along with Douglass and Toussaint L’Ouverture. In 1971, the Black Academy of Arts and Letters began a Hall of Fame. Williams was one of its first six inductees along with Frederick Douglass and W. E. B. Dubois. Booker T. Washington and W. B. Dubois were inspired by him. In the 2016 film, The Legend of Tarzan, Samuel L. Jackson played a fictionalized Williams who accompanies Lord Greystoke (and Jane! and Tarzan’s childhood animal friends) on an action-packed adventure (the film was rightly-panned by reviewers). Through his “Open Letter to King Leopold,” Williams lit the fuse on a slow burning incendiary device that finally, decades after his death and long after his name was forgotten, exploded the structures of European colonial exploitation of Africa.

A portrait of Williams now graces the hallway leading to the Andover Newton Seminary offices. Andover Newton will honor George Washington Williams in a number of ways over the coming years.

Follow our social media for upcoming announcements. Learn more about the George Washington Williams Summit for Black alumni/ae of Andover Newton on the event page.